A Comparison of Learning Strategies

This gallery contains 1 photo.

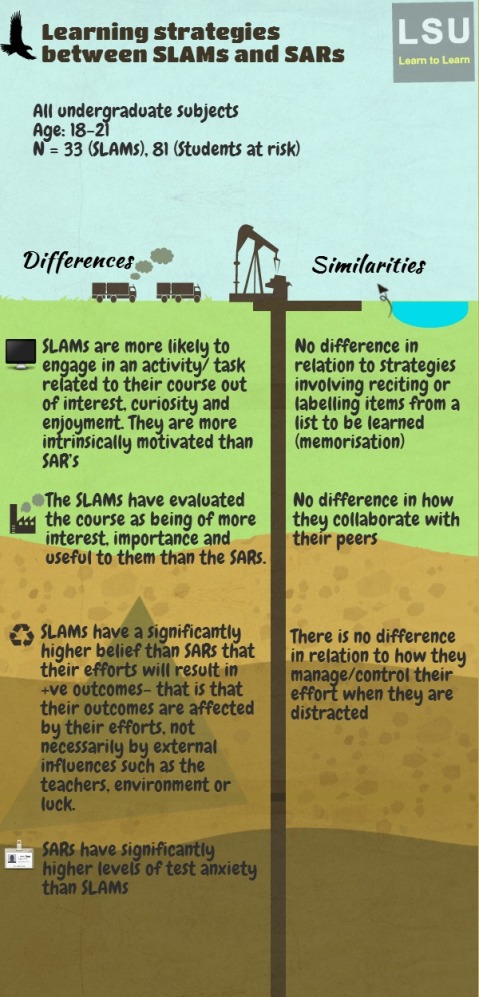

Study by Carol Witney & Wei Wei Infographic By Wei Wei The infographic below is of an investigation into the learning strategies employed by two groups of students at our university. The primary research question was, What underlying variable(s) can explain the academic performance between Student Learning Advice Mentors (SLAMs) and Students At Risk (SARs)? And, more […]

Carrying Your Weight: Academic Style

By Sam Graham, LSU

In the LSU, we often help students with their essays, which is much the same as coaching weightlifting.

We refine students’ writing techniques so they can express their ideas in the clearest, most convincing way possible. We don’t write the essays for them, though.

Weightlifting coaches refine lifters’ lifting techniques so they can lift the most weight possible. They don’t lift the weights for them, though.

Reading A Theoretical Approach to the Coach’s Cue, I see that we face a lot of the same challenges as weightlifting coaches.

Weightlifting at the Maccabiah Village, from the Government Press Office (Israel), under Creative Commons license

Lost in translation

In the weight room

What a lifter hears might be quite different from what their coach says because they have different ideas, or models, of an ideal lift. The coach provides cues based on their model, formed by their education and experience as a lifter. The lifter has their own model, and cues are interpreted under this model. Where the models differ, a cue might mean something quite different. Sometimes, past training of the lifter can make their model quite different from the coach’s, and this can interfere with the coach’s cues.

In the LSU

Similarly, what a student hears might be quite different from what their advisor says because they have different models of an ideal essay. Also similar, past education can interfere with the advisor’s cues. With a less-than-ideal background in academic English or with academic experience only in a different tradition – common in Vietnam – other conceptions of academic writing can interfere with their understanding of our advice. On the other hand, If they’ve had good English teachers, this makes our job easy because we can provide short cues and they know what we’re suggesting (“Where’s the topic sentence?”).

Know your student/lifter

In the weight room

As a weightlifting coach and a lifter build a relationship, the coach develops an understanding of what the lifter understands. Meanwhile, the lifter’s lifting model aligns with the coach’s model, allowing them to more quickly and even reflexively understand each other.

In the LSU

I still see students I taught in the English programmes, where I worked before moving to the LSU. Knowing their background means I know the wider context of their writing issues. They also know what to look for in their writing if I say simply “Explanation?” and don’t need a full explanation of the importance of explicitly explaining the connection between evidence and a contention.

Speak softly and carry a big stick. Or don’t. It depends.

In the weight room

Some lifters like a calm space, others macho chest bumping. Some like loud, sharp pointers, while others prefer quiet, technical pointers.

In the LSU

The ‘treatment’ for the same issue, and how I deliver it, is rarely the same for students I know.

Everything we see is a perspective, not the truth.

In the weight room

The coach and the lifter’s perspective is quite different. The coach watches while the lifter feels the weight. A good coach will use their own experience as a lifter to make cues that make sense from the perspective of being under a weight. Telling the lifter what the outcome should look like won’t always work since the feeling of the weight is far more immediate. Getting them to make small changes can help ‘trick’ the lifter into making far bigger ones.

In the LSU

It’s also easy to forget that our view as an advisor is quite different from the student’s. Without a cloud of facts from the research, it is easy to see how arguments might be rearranged or tightened. For the student, there are far more moving parts – both in the essay and in their notes – to consider.

We can also help our students write far better essays with small tricks. For example, I’ve had success getting students to link their supporting arguments to their thesis – a quite difficult concept – by telling them to simply make sure that the keywords from their thesis statements are in each paragraph. It’s easy to do this, but difficult for them to do it without linking the ideas.

…

The principles here are, I think, universal. I can’t think of teaching contexts where the following won’t make for better teaching and learning:

- Know how your students see themselves

- Know how your students see their work

- Know how your students see you

- Perspective matters

- Small changes lead to big changes

- Prioritise what needs to be changed

- Speak their language

- It isn’t just what you say, it’s how you say it.

Reflecting (on) microaggression

By Ian Handsley Ian lives in a small Japanese fishing village with his wife and 4 kids. Just enjoying a spot of house husbandry at the moment, but will be back at the higher-education coal face soon. Higher Education Innovationist and former member of the LSU. I stop passersby in their tracks. I attract the stares […]